Recently, I started Blood of Elves, the first in The Witcher series. Quickly, I was struck by the author’s vocabulary. As in page 2.

“… a horse’s belly and a frayed girth flashing by above her head, then another horse’s belly and a flowing black caparison.” A bit further in: “the pounding of horseshoes, fetlocks and hooves flashing past.”

Girth (all definitions from Merriam Webster): a band or strap that encircles the body of an animal to fasten something (such as a saddle) on its back.

Caparison: an ornamental covering for a horse.

Fetlock: a projection bearing a tuft of hair on the back of the leg above the hoof of a horse or similar animal. Or, the joint of the limb at the fetlock.

It’s a perfect example of choosing the best word without looking like you wrote with a thesaurus in hand. Sometimes, a writer falls into the trap of thinking the best word is the most obscure, the one with the most syllables. Instead, the best word often is the most specific word.

Note that Andrzej Sapkowski (author of The Witcher series) did not feel “abdomen” was better than “belly”. “Belly” won over “stomach”, even. Reasons why might include balancing the 5-star words with “normal” ones, care that the reader does not need to look up too many words per sentence, or… it might just be that “belly” has more character.

Word choice isn’t about choosing the least-known word; it’s about choosing the most descriptive. The most precise.

Dictionaries are only helpful when you have the word in hand. Thesauruses will not help you with girth (as it pertains to husbandry), caparisons or fetlocks.

“What do you call that thing that goes around a horse’s stomach”—if you thought to ask and didn’t just call it “the belt around the horse’s stomach”—led me to horse colic and information on a horse’s gastrointestinal tract using web search. ChatGPT got me there. I also learned we call it a “cinch” in Western riding. (Thanks, Chat.)

Inquiring about a specific joint of a horse’s leg, or what that one tuft of hair is called, might be more difficult.

There’s a surprising lack of books or websites offering labeled illustrations—both whole views and dissected diagrams—that make vocabulary discovery easier. Often, we stumble on new words in the stories we consume.

Shoutout to Severance for giving me “transom window”.

And while books and film are sources of that specific word, hoping you stumble on “caparison” while writing the battle scene of your renaissance-inspired fantasy novel is less than efficient.

The following are some of my favorite resources as a writer. This isn’t an ad, I’m not affiliated with either publisher or author. I just think they’re books writers should have or check out while writing.

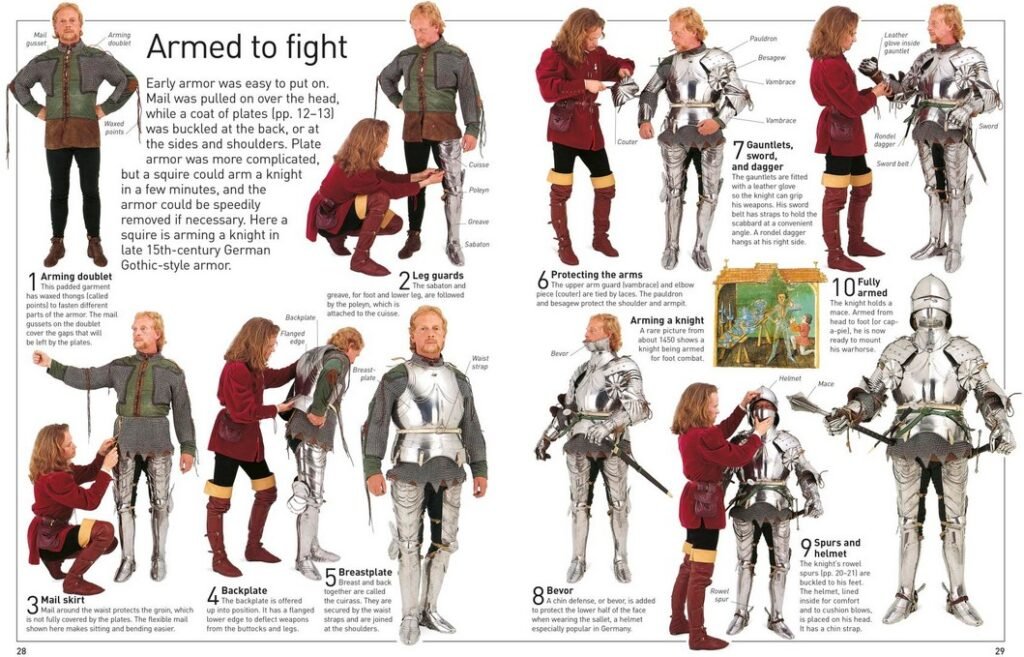

I grew up with DK Eyewitness Books, and apparently they are still making them. Which is great, because they’re a treasure. This picture, from Knight, is just par for the course of each of these books, with subjects ranging from space, to the human body, to Islam, to the elements, to insects… and on and on.

They’re perfect. If there’s one on horses (of course there is), I don’t doubt “fetlock” is in there.

Suddenly, you’re accurately describing the process of putting on plate armor—there’s no “throwing it on” and running outside.

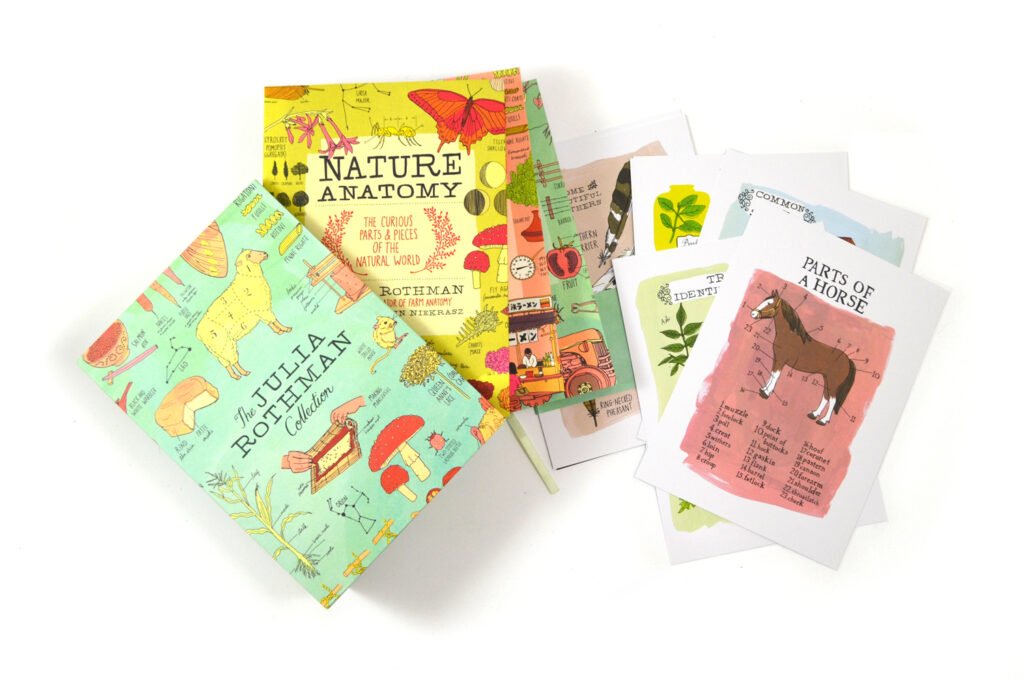

Julia Rothman is an author and illustrator who makes beautiful, informative books.

I knew I was going to write about this series when I opened my google doc. Imagine my surprise when I saw “fetlock” in the image above.

I own Nature Anatomy. Some of my favorite labeled illustrations include: “The Life Cycle of a Mushroom” (next to an illustrated crash course on mycelium, and an illustration labeling a mushroom’s anatomy), the leaf identification guide, and “The Anatomy of a Flower.”

I only warn that you might get distracted learning about the constellations while working.

Oh no.

Truly, when it comes to learning very specific vocabulary, I find the information more accessible, easier to find in these books than tailoring the perfect search query, the question occurring to me in the first place, scrolling to page 5 of the results before I find it, and then reading the accompanying essay to sift for that word.

And easily more pleasurable.